Improving Work Capacity, the Mileage Paradox, and the Progression Zone

This post was originally written by Jesse Firestone and published at jfireclimbing.com. Jesse is a C4HP partner coach. You can book a technical review or coaching with him through Camp4.

Henry George said, “Man is the only animal whose desires increase as they are fed; the only animal who is never satisfied.”

Now, obviously Mr. George didn’t own a dog… if my partner and I get home at different times, our dog will try to convince the later arrival that the earlier one didn’t already feed him dinner.

Canines aside, I think the quote is dead on. Climbers love to do more and more stuff – even long after it’s damaging their progression.

Perhaps economics, which often deals with resource consumption, is a good lens to look at this. Jevon’s Paradox suggests that as use of a resource becomes more efficient, demand for that resource goes up, negating any reduction of the use of that resource.

As an example, as cars become more fuel efficient or gas becomes cheaper, the demand for travel goes up, and the same amount of (or more) fuel is used up.

Another example is when water reservoirs are built. This should put communities at lower risk for water shortage, but often it leads to more housing development and water availability shrinks anyway.

The same is true in climbing.

The mileage paradox

As one becomes more effective at getting through submaximal climbs in fewer tries, one expects to do more of that level of climbing in a given day. The end result being not that less energy is spent on a mileage day, but actually that the mileage days get longer and harder – and even more energy is spent. I’m as guilty of this as anyone.

Several years ago I took part in an outdoor bouldering competition, where the goal was to do as many climbs as possible above a certain grade in an 8 hour period. We were in teams of three, and all team members had to finish a climb for it to count. Our team did 127 V-points of V4 and up that day. It was an incredible day of climbing, and I pushed my physical limits to the brink. I also completely sabotaged the rest of my season and re-inflamed numerous old injuries.

We all have to decide if these experiences are worth it in the end. Nothing is free. If we never pushed into fatigue, we’d never improve our capacity. If we never pushed into challenge, we’d never get stronger. If we never pushed into risk, we’d have a hard time achieving true greatness. “You have to risk it to get the biscuit,” I hear the crusher kids say. And that’s all good – but one can’t live on biscuits alone.

Tyler Nelson (@c4hp) calls this “hoarding mileage” and it’s the perfect label. Hoarding really is what it is. Doing a ton of climbs is great if that’s all you want to get better at, and you don’t mind resting a lot in between days. But it’s mostly egoistic. So what about trying hard?

Projects

Jevon’s Paradox holds true for projects, too. As one becomes more effective at finishing limit climbs, one expects to be able to climb harder and harder things. The end result isn’t that less psychological and logistical resources are spent on projects, though.

In fact, these resources are used up even faster, sometimes in a disturbingly small number of actual attempts. As draining as it is to spend hours bashing your head against a hard project, it’s even more frustrating and discouraging to find that you’re powered down after just a few tries on a true-limit project.

Climbing grades aren’t linear, and climbing challenges aren’t either. Terrain and skills have just as much to do with the injury risk and fatigue incurred by a given problem or route than the grade. That said, grade is a primary indicator that we can use to simplify thinking about workload.

One try on a V12 is not the same cost for me as one try on a V10. I might only get a handful of tries on a V12 project in day, and it might take me a few days to recover from those tries. That means I might only get to try my project maybe 10 times in a week! And that’s assuming I barely do any other climbing for my sanity.

In this way, too much projecting will actually cause capacity to go down. We know that in order to grow and progress, we need the capacity to do more stuff. That means increasing our workload over time is essential. We also know that climbing volume is one of the chief risk factors for injury. This is a delicate balance we have to strike.

Learning from my mistakes

When I was younger I used to regularly do “centurion” workouts: I would do 100 V-points of climbing of a certain grade (usually V7) in an hour. Sometimes I would follow this up by doing another power hour at a reduced grade like V6. At the time, I climbed around V10 max. That’s something like 30 moderately-hard-for-me boulder problems in a session!

In retrospect, most of that climbing was a waste of time. I was so tired by the end that all I was teaching myself was to hold on no matter what. A valuable skill, to be sure, but not one that should be visited so frequently, and especially not when the fatigue is already so deep.

Fatigue of that depth runs contrary to good movement skill practice. You can practice pushing through being tired, or you can practice your top-end movement perfection – but you can’t practice both at the same time.

(A puzzling thing about climbers and training culture is that even though I just laid out a compelling reason not to do that centurion workout, I’m sure that just by mentioning it, several readers of this post will decide that it sounds “fun” and try to do it anyway.)

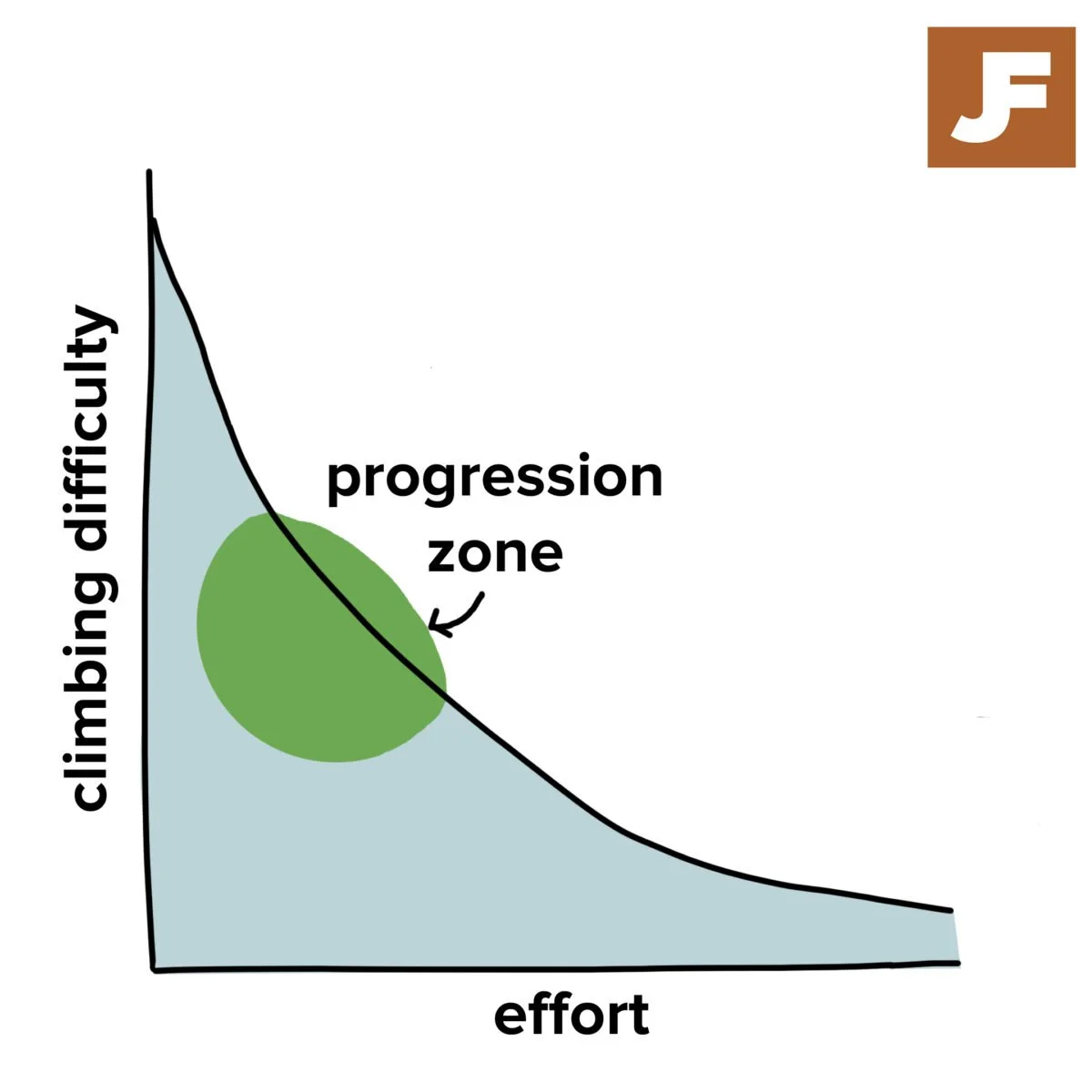

If I could go back, I’d tell myself instead to focus on the progression zone. This is the zone of climbing that’s close to your max, but still reasonable to get done in 1-3 sessions. These climbs are too hard for a “centurion” type of workout or 4x4s. At the time, my zone would have been around V8 and V9. Trying several of these in a session, maybe sending a few, and then calling it before I got tired, would have been the best way for me to keep getting better. (The “calling it before I got tired” part is absolutely crucial!)

If I’d had a bouldering trip coming up and needed to bump my capacity, I could have done that by splitting my time between progression zone and mileage zone climbing at about an even ratio. I still would have kept my mileage zone climbing effective, analytical, and restful, though. No timers or mega days. Just focusing on the quality of my movement, but at a slightly lower grade, and letting myself get slightly more tired before finishing each session.

If I’d wanted to really test my limit, I could have done that by just cutting the number of tries even further on a progression day, and trying a V10 or V11. This would be fine for a few sessions or a couple weeks, but not sustainable indefinitely.

The capacity prescription would be different for other kinds of climbers; sport climbers get more mileage automatically, but also need more in general. Mixing in mileage days regularly is probably wise for a sport climber in most seasons. This will help with the novel skills of clipping and onsighting, and skills like project selection and skin management that are often more taxing than in bouldering due to higher investment cost. Trying to maintain project level climbing indefinitely is psychologically and physically exhausting for a sport climber. But, because sport climbing is unlikely to be as taxing in the top end energy systems, and generally less injurious, the progression zone is a bit closer to one’s limit.

Big wall and alpine climbers could actually consider their progression zone and their mileage zone the same thing, since persisting with good technique through sustained suffering is a primary goal.

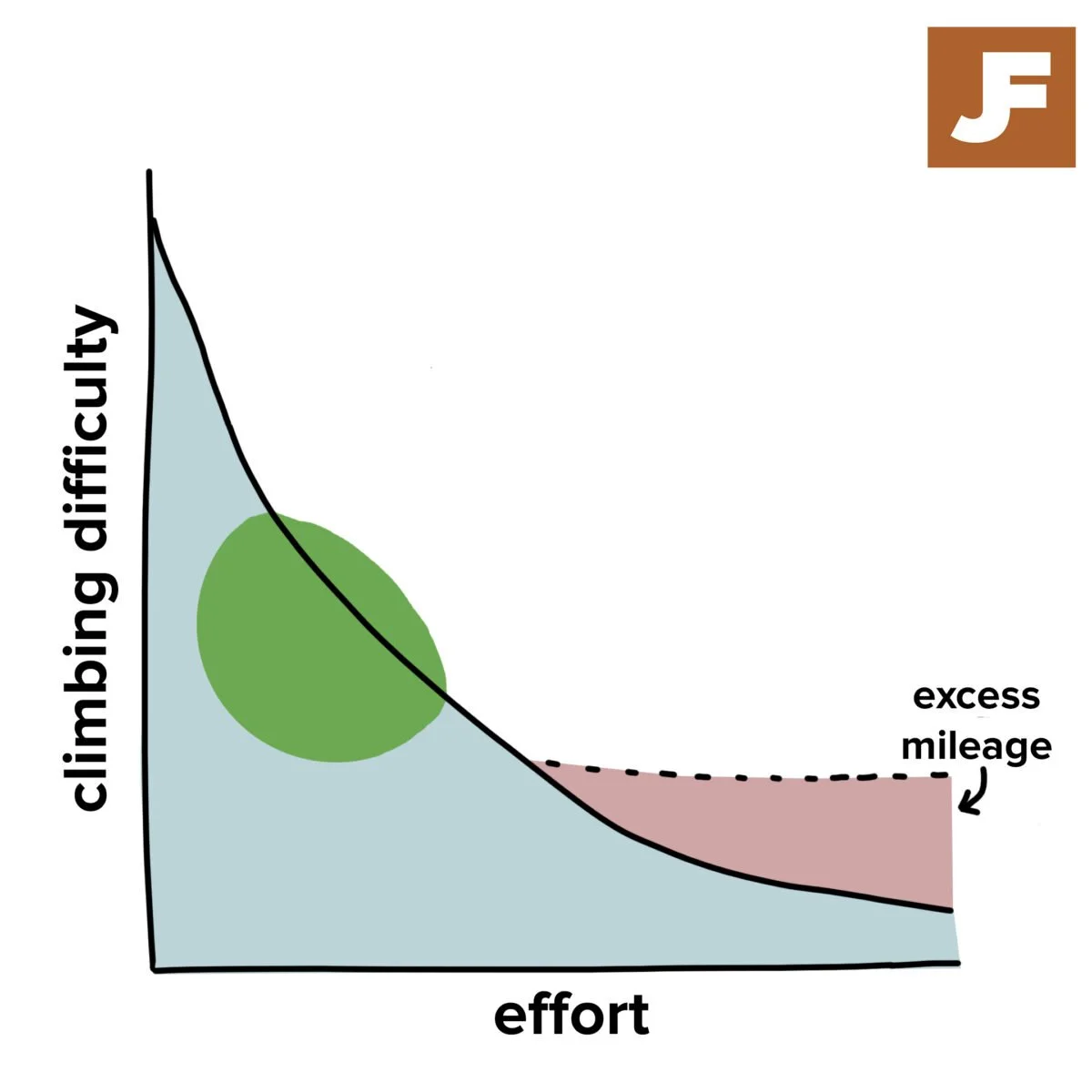

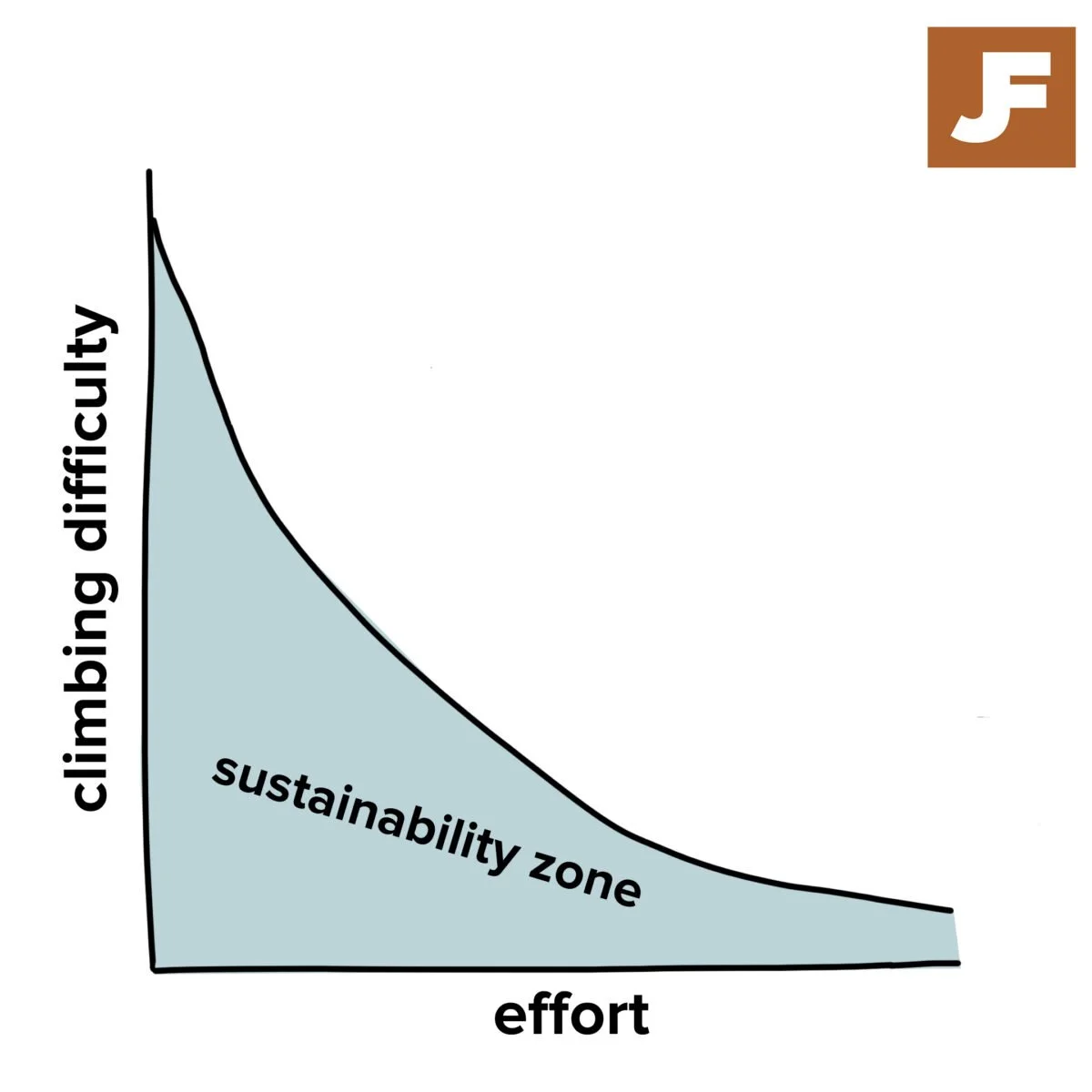

For intermediate to advanced boulderers, though, it’s probably wise to limit mileage. This idea is tough to come around to, because for the first chunk of our climbing progression, more mileage is a great way to improve skills. At that stage, we aren’t fit enough yet to dig the hole so deep that it does major damage. If you’re projecting V3, everything under the “sustainability curve” in the graph above doesn’t constitute that much total climbing at your average gym or crag. But when you’re climbing V8 or V9, that sustainability zone represents a massive amount of climbing.

This is where Jevon’s Paradox becomes evident. We carry that self-expectation of getting it all done with us as we journey upward through the grades, even until that mileage becomes toxic to our success. It’s costing us the very resources that we need to make those tiny gains in our progression zone.

Summary: If you want to get better, you can’t just do more forever.

Takeaways:

Resist the urge to do more and more stuff

Do the stuff that counts, and do it well

Spend most of your time in the progression zone

Mileage is good sometimes, but be considerate with it

Good tracking of your workload is essential if you want to increase it

Nutrition and sleep should be the priority when increasing workload